Introduction

For a long time architectural drawings have only been appreciated from a technical point of view, as preliminary plans for building.

'Frequently austere, sometimes of an unusual or abstract form owing to their geometrical economy, architectural drawings are possibly the moste intellectual constructs in graphic art. They necessitate a new sort of interpretation : the plan, the section or the profile of a building is deciphered analytically but also imaginatively, for the onlooker must reconstruct these details in his mind in relationship to the edifice as a whole. The rigour and the technical aspect of such projects impose their own specific language' (1).

Perspective line drawings, ink washes or watercolours, on the other hand, are easily comprehensible to everyone.

Architectural drawings have nevertheless always attracted the attention of some scholars and a few art collectors. The most recent approach consists of considering them as an art form on an equal footing with the drawings of painters and sculptors. Such drawings are of vital documentary interest for the increasing number of historians of architecture studying existing monuments, buildings that only existed in project form or have disappeared, and the men responsible for them.

It is high time to appreciate the importance of preliminary studies which allow us to follow the birth of a project and understand the artist's intention at its source. For many years the manuscripts of famous writers, painters' sketches and the original scores of musicians have been preserved. Their conservation has permitted a deeper knowledge of these artists while their works have been the object of increasingly thorough study. Architectural work deserves as much attention.

Initial plans and projects are given a better chance of survival.

The surviving drawings and documents covering architectural activity in the 19th and 20th Century which we are taking pains to assemble and preserve represent only a tiny proportion of what was produced during this period.

More often than not practises close down and archives are dispersed when architects change address, retire or die. Some archives are destroyed by architects themselves, after expiration of the ten year period of responsibility. The action of time and men conspire against the preservation of archives. Let us hope that what we collect may be a contribution towards a picture of architectural development.

Architectural drawings come frome several sources. The can be by the architect himself, who may or may not have signed them. We only consider drawings to be the architect's own work when confident of their authenticity. The drawing has frequently been produced by an agency whose director was assisted by colleagues who with their own abilities and tastes attempted to express their employer's architecture. The director has to provide a sketch, correct proofs and give his final approval. But even signed and approved, the drawing remains a workshop product. For many years painters worked in exactly the same way. We know, for example, the names of the draughtsmen responsible for drawings in Auguste Perret's practise because the work is relatively recent. But for earlier periods attribution becomes more complex and muddled. Numerous arguments arise as to whether responsibility for a project should be attributed to the director of a practise or another party.

We must also remember that plans are ephemeral documents which in the architect's view do not need to be kept once a project is completed. Plans which have come down to us have suffered from careless handling or their fragility.

Paradoxically the architectural project itself, apparently solid and built to last for centuries, is in itself a fragile product. In most cases it is eventually transformed and deviated from its initial concept. The plan given at the outset may no longer correspond to present circumstances. Changes in function often require structural changes ; a monastery is turned into a town hall, a station, a museum. A building may also be destroyed to free the plot for another use. Buildings which survive intact are the exceptions. Drawings remain their most eloquent testimony.

These graphic documents allow us to rediscover the sequence of ideas which, from initial sketches to completion, have gone into a building, a series of buildings or the complete work of an architect. Considered separately they constitute proofs for dating constructions and identifying their authors. Drawings may often permit a better appreciation of the architect's stylistic concepts than the finisched work itself. The latter is the end result of all sorts of compromises : financial, the whims of the contractor, the modification of plans during construction and, often, as have already said, subsequent transformations.

Architects frequently produce plans which are never realised : the client may abandon the project, the architect may fail to win a competition. His proposition may simply remain unnoticed. Training projects suffer the same fate. All this work constitutes what has been called 'paper architecture'. Such documents are extremely valuable for the historian and the art enthusiast because they provide an appreciation of the architect's concepts and his references. These studies contribute to the appreciation of the taste of a period and the development of style.

As everything is possible on paper, we comme to architectural fantasies which have no other purpose than the expression of a daydream or a utopic vision. These flights of fancy, bearing in mind the development of taste and techniques, may at a certain moment become the source of inspiration for a perfectly rational architect, who will interpret them. Visionary or practicable, they may also be a diversion, a pipe dream for an architectect who cannot express himself fully through commissioned work.

A final category of drawings comprises those of ancient monuments. Travel sketches in pencil, pen or watercolor, geometrical plans of entire buildings or architectural details, the reconstitution of monumental groups, 'dispatches' by residents of the Académie de France in Rome, works submitted to the 'Salon'. Such reports on the condition of a monument can help in understanding or restoring it.

As the architecture and architects of the 19th Century become better known to an ever wider and increasingly inquisitive public through lectures and exhibitions, some directors of public and semi public organisations have responded by starting to set up real architectural archives. The example set by the creation of the 'Archives de l'architecture moderne' in Brussels proved a stimulus. Like many other countries, France is also nurturing the project of a museum of architecture.

Such projects are very difficult to realise on account of the enormous and continually renewed quantity of stocks which have to be received, preserved, catalogued, restored and made available. Given the impossibility of accepting every single document it would be best to choose from among documents from the most representative architectural practises of their period. That is the policy we are pursuing.

Until a central organisation is set up, action must be taken immediately, for large stocks are being lost. Such conservation can obviously only be taken on with the coordinated and concerted help of those with a vocation for such work. It would not be appropriate to designate them here. I make an exception, however, for two cases ; the collection of documents, architectural and construction drawings at the Centre National des Arts et Métiers constituted by Jean-Baptiste Ache and the Fondation Le Corbusier which has grouped together the entire production of this architect, including all his texts and most minor sketches.

There are well known precedents for collections such as these. The Tessin collection in Stockholm was created in the 18th Century by the French Ambassador of the same name who acquired all the drawings he could from the practises of Parisian architects to serve as models for their Swedish colleagues. The Tessin collection is an essantial reference for anyone working on 18th Century French architecture.

A comparison can be made with the collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects, which now contains over 250,000 drawings. Started in 1834 the collection flourished after 1950.

The recently created Canadian Centre of Architecture has also devoted its efforts to assembling the archives of contemporary Canadian architects as well as older architectural drawings and photographs. Its collection is already wide ranging.

Collections of note in France include those of the library of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts de Paris, the Cabinet des dessins of the Louvre Museum, the Cabinet des estampes et des dessins at the Bibliothèque Nationale, the Union Centrale des Arts décoratifs, the Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication (direction du Patrimoine) and most recently the 19th Century Musée d'Orsay.

Michel Massenet, Conseiller d'Etat and former President of the Caisse Nationale des Monuments Historiques et des Sites, chosen in 1979 by the Prime Minister and the President of the Republic to draw up a report concerning the establishment of architectural archives, wrote :

"... the best approach as regards the compilation of these archives, in as much as it must remain a voluntary procedure, is certainly of a professional nature. This process can be accomplished in the name of 'corporative' ties, of technical competence or a sort of historical legitimacy. The Academie d'Architecture, a private organisation and successor to the Société Centrale des Architectes provides an example of an endeavour based on the 'professional connection'... Well placed to receive gifts from heirs and former members, the Académie has developed its valuable collections rapidly and along clearly defined lines towards a testimony of modern creation."

This activity derives from an already well established tradition. As early as in 1843 the Société Centrale des Architectes devoted itself to the creation of a library thanks to purchases but especially donations by its members. The first catalogue was published by Frantz Jourdain in 1898 an included the majority of architectural books and magazines published during the 19th Century. The library began stocking original drawings by its members and collecting medallions, engravings and photographs concerning architecture and architects.

In 1906 one of its archivists, Charles Nizet, implemented the policy of acquiring works through purchase or donation and bought the important collection of drawnings by Hector Horeau at public auction.

In 1962, thanks to Claude Le Coeur, then archivist of our assiociation, we received the donation of a considerable part of the Destailleur family's library, along with albums of original drawings and photographs of the works of this architectural dynasty.

In 1976, as a contribution to the exhibition, then in preparation, to commemorate the centenary of Henri Labrouste, Madame Yvonne Labrouste gave us most of the works by her husband's grandfather in her possession (3).

She completed this extremely generous donation sometime later by giving us everything concerning the career of our former president. The documents included dispatches from Rome, plans of Ancient and Renaissance Italian monuments, those of his houses and commemorative monuments and his entire library. We also received handwritten archives comprising correspondence and reports plus all the official and unofficial documents which marked the major steps in his career, along with a number of personal possessions. In addition we were given significant plans and documents concerning the career of his son Léon and drawings by Théodore, his brother and Grand Prix de Rome, plus an ensemble of drawings and watercolours of Italian monuments by Adolphe Goujon, an architect who worked in collaboration with the family.

To complete the series of drawings which often concerned a single monument and had been split up when the inheritance was divided, our colleague Léon Malcotte-Labrouste, Henri's great grandson kindly left his part of the inheritance with the Académie to allow a more thorough study of his forbear's life and work.

It is thanks to Madame Antoinette Boutterin that we received the stock ofs works of Bouwens van der Boijen.

The 20th Century collections, which will be the subject of the next catalogue, are considerable, and complete as regards drawings and written material. This is the case in particular for Léon Jaussely, Henry Prost, Maurice Boutterin, Roger Expert, Jean Niermans, Marcel Lods, Henry Bernard, Michel Andrault and Pierre Parat with whom we broach contemporary urbanism.

It is now customary to ask every new member of our association to assemble all possible material from the family of the member he has replaced and to offer, on the occasion of is installation, representative drawings of his own work. At the end of their careers some members complete this donation with drawings and photographs of what they esteem to be their best work.

With our members' help we also collect material relating to the teaching of architecture, exhibitions of the former Ecole des Beaux Arts, and workshop models in order to found a sociological study of this category of artists.

We have to be constantly on the look out for worthwhile pieces so as not to lose a large number of documents of vital interest for the history of architecture. It is obviously impossible to prevent works being dispersed - even if this dispersion reduces the risk of destruction. It is necessary for drawings and documents in general concerning the same period, an architect and his school or a particular building to be grouped together, whence the urgency of establishing systematic catalogues.

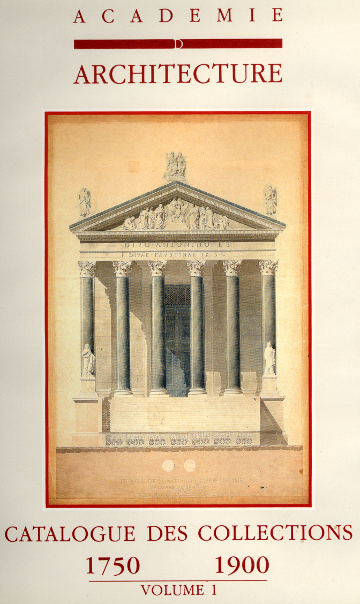

The Académie, which is sollicited by numerous official organisations to loan parts of its collection for exhibitions, consulted by letter and by an ever increasing number of visiting researchers, many from American universities, considers it would be most useful to publish catalogues of its collections as the R.I.B.A. does. Its first volume, a substantial undertaking, couvers drawings and documents from the last quarter of the 18th Century to the beginning of the 20th Century.

By taking into account the steps in the training of an architect and the diverse aspects of his professional activity we propose a classification in which all the drawings of our collection can be brought together.

Drawings prior to 1800

Still thinly represented : a candlestick by the painter Jean-Charles Delafosse (1734-1789), a project for a catafalque to the memory of Louis XV, showing two sides, by Charles Michel-Ange Challe (1718-1778), a particularly fine interior view of the Pantheon in Rome by Jean-François Chalgrin (1738-1811) and Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713-1780) a wash drawing, plan and vertical section, of the monument of the Countess Mathilde de Toscane at Saint-Peter's in Rome commissioned by Urban VIII from Bernini in 1633. By Charles Percier (1764-1838) we possess the studies of Ancient remains kept at the Villa Albani in Rome.

Two albums deserve particular mention : that of Augustin Caristie contains remarkable drawings of monuments and houses executed during his stay in Rome at the beginning of the century. The second, from the Labrouste collection, concerns a project for the reconstruction of the Château de Marly by an unknown late 18th Century architect.

The plans for the lycée of Turin, draxn up the 20 frimaire of the Year XII (December 12 1803) by L. Lombard when the city was the capital of a French département, executed in the style of late 18th Century architectural drawings, serves as a transition.

The projets of the Ecole - successively Royal, Imperial and National - des Beaux Arts in the 19th Century

They include the study of orders, sketches for admission and competitive examinations such as the Labarre, the Delaon, the Chenavard, 'L'Américain' and all the other steps which lead up to the Grand Prix de Rome.

L'Académie d'Architecture has a large number of student projects carried out in the Beaux Arts workshops during the 19th Century.

The journey to Italy

Learning about the monuments of Ancient Rome but also Renaissance works inspired by the former was the goal of many architects who travelled to Italy. Each year the prizewinner of the Grand Prix de Rome was officially sent to Italy as resident of l'Académie de France. Others set out on their own initiative despite the expense and substantial difficulties of such a journey. These men of art expressed themselves by drawing plans and reconstitutions. Others made sketches and watercolours to conserve their souvenirs in much the same way as people nowadays take photographs.

Dispatches from Rome

The winner of the Grand Prix stayed for four or five years at the Académie de France in Rome and each year had to send a meticulously executed plan of Ancient architecture to the Académie des Beaux Arts. For the first year a detail had to be studied - a capital, frieze, tomb - leading up, in the fourth year, to a plan of a large monumental ensemble and its restitution. In his fifth year the Grand Prix holder was able to treat a subject of his choice.

At first these architectural studies were done in Rome, then in the rest of Italy, Greece and eventually the Middle East.

Among the fourth year dispatches the Ecole des Beaux Arts possesses drawings stipulated by the Académie des Beaux Arts. Other drawings, completing these series were kept by former Grand Prix students. Some of them have come down to us via their heirs. The Académie d'Architecture has, for example, among others, dispatches by Marcel Lambert, Henri Labrouste and Hector Lefuel.

The journey to Greece

Very few architects were able to travel to Greece until the second half of the 19th Century. From this period we have a magnificent watercolour painting of the propylaeum side of the Acropolis of Athens showing the state of the approach prior to the discovery of the Beulé gate, date 1845 by Louis-Alfred Chaudet (1812-1891) and a watercolour perspective of the Greek temple of Corinth. We also have an album by Alfred Normand of a journey from Athens to Salonika (1851) including a large number of drawings all the more interesting as they depict buildings which existed during the Ottoman occupation.

Travels in France and Europe

Charles Rohault de Fleury (1801-1875), architect of the first conservatories in the Jardin des Plantes, and his son Georges (1835-1905) were great travellers, as shown by 28 albums and books of often elaborate sketches. They too went to Italy. 12 sketchbooks ranging from 1842 to 1870 contain the fruit of their trips to cities such as Venice, Padua and Vicenza. An entire book is devoted to Rome. The two men were also particularly interested by Switzerland and brought back three albums and a book of sketches of chalets from their journey of 1852. They also visited Belgium (1848) Germany (1852 and 1857) Britain (1851) while paying considerable attention to France, to which several sketchbooks between 1846-1855 are devoted. A whole album containing extremely fine watercolours is devoted to Paris.

Plans of historical monuments

Their execution was not restricted to architects officially in charge of the upkeep and restoration of historical monuments and whose documents are kept at the Direction du Patrimoine at the Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication. Many architects made plans of monuments they found particularly interesting and which were intended to appear in the annual salons of the architectural department. The plans of Blois by Léon Vaudoyer and those of the Château de Nantes by Joseph Deverin are two such cases.

Architectural projects concerning works, constructed or not

Although there are relatively few initial and research sketches in our 19th Century collections, we do possess a large number of project drawings, almost all in colour and executed with extreme care, notably one by Percier (1764-1838) and Fontaine (1762-1853) for the fireplace of the grand cabinet of Napoleon I at the Tuileries and the project, carried out between 1823-37 by Hippolyte Lebas (1782-1867) of the church Notre-Dame-de-Lorette in Paris.

The collection of drawings by Hector Horeau has been researched in the terms of a contract with the Comité de la Recherche et du Développement en Architecture (C.O.R.D.A.). This research enabled an exhibition to be held at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs and an extensive catalogue to be publisched. I completed the study of the life and work of this architect in Horeau précurseur publisched by the Académie d'Architecture in 1981 (4).

A further example is a finely coloured drawing of the esplanade of Les Invalides in Paris, around which Alphonse Crépinet (1826-1892) planned in 1870 to group together ministry buildings, and a particularly fine watercoloured section by Ernest Coquart (1831-1902) for the installation in the covered courtyard of the palais des études at the Ecole des Beaux Arts of the 'Musée des moulages".

Among private buildings 19th Century Parisian 'hôtels particuliers' have pride of place. We will mention in particular the Parisian "hôtels' Rouvenat et Vilgury by Henri Labrouste and the famous hôtel Yturbe (1886-1889), avenue du bois de Boulogne, now demolished, by Ferdinand Gaillard (1836-1912).

The Académie has a number of major works by William Bouwens van der Boijen (1834-1907) such as the extremely finely coloured interior decorations for the Vanderbilt building in New Port USA, the plans of the building at 27, quai d'Orsay Paris and parts of the interior decoration of the town house he built for himself at 8, rue du Lota Paris.

Imaginary works and architectural utipias

Edmond Corroyer (1835-1904) drew up a project for a completely imaginary royal seaside resort residence in one plan and three large vertical sections, in gouache. 'Fantaisies architecturales' is the title given by Henri Mayeux (1845-1929) to an architectural flight of fancy of which 14 original and amusing drawings have come down to us.

Architectural details

Among these some very successful coloured studies concerning stone cutting and frameworks by Eugène de Crémont (1821- ?) when he was a student at the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures and the Ecole des Beaux Arts.

Old photographs

Some are reproductions of original drawings which have since disappeared, others show 19th Century buildings captured on film by the great names of the history of photography. They include two views of the Palace of the Dolmabahce in Constantinople taken by James Robertson in 1855 and others of his works conserved by Alfred Normand.

Manuscripts, medallions, effigies and architects' personal belongings

In addition to texts which are important for the history of architecture, we possess bills of quantities, reports letters and autographs of the greatest 19th Century architects. The whole of Henry Labrouste's archives concerning his teaching and work constitute a perfect source for those interested in this architect and his influence.

Our collecion of medallions is intended to commemorate remarkable monuments, famous or reputed architects, theorists and historians of architecture, organisations of architects an building professionals.

We have also received donations of marble, bronze, terracotta and plaster busts and oil portraits of famous architects and a large series of photographs of architects.

No collection is ever finished and each of the sections described above can accomodate additional pieces. We hope this catalogue may serve as an appeal fort complementary material, and contribute in itselfs and by encouraging emulation to the safeguard of an important part of our heritage. Let us preserve our memory of architecture.

Paul DUFOURNET

Notes

Dessins d'architecture du XVème au XIXème siècles. Catalogue of the exhibition of the Cabinet des dessins du Louvre, 1972, Introduction.

Exhibition Henri Labrouste organised by l'Académie d'Architecture et la Caisse nationale des Monuments historiques et des sites, hôtel de Béthune-Sully, 1976.

Catalogue taken from the Revue des Monuments historiques.

HECTOR HOREAU (1801-1872). Study carried out at the Académie d'Architecture under the direction of Paul Dufournet (C.O.R.D.A. contract). Catalogue of the drawings and representative works of the architect par Paul Dufournet, Françoise Boudon and François Loyer, supplement to Cahiers de la recherche architecturale N° 3.

Exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 1979, prepared by Françoise Boudon, François Loyer and Pierre Granveaud. Paul DUFOURNET, Horeau précurseur. Idées, techniques, architectures, Académie d'Architecture, Actualités, Paris, Ch. Massin éd. 1981.